INSI issues coronavirus advisory

INSI issues coronavirus advisory

The coronavirus is spreading around the world and is now present in 77 countries and on all continents except Antarctica. As the situation is constantly evolving please ensure you keep up to date with the health authorities’ advice in your own country.

INSI members are cancelling/carefully considering unnecessary travel to protect staff, preparing home working strategies and drawing up contingency plans if major events like the Olympics should go ahead, all while dealing with staff fears and a news agenda almost entirely driven by the fight against the virus.

Background

Months into the outbreak, health authorities still have limited knowledge of how the virus works and exactly how it is spread. Covid-19 has an estimated average fatality rate of around 1%. In practice that percentage is believed to be lower in young and healthy individuals, but higher in people over 60 and people with underlying conditions, according to the UK Chief Medical Officer.

To put the figure in context, SARS, another coronavirus, had a much higher mortality rate of around 10% but its symptoms were very easily identified and its spread was very limited. Around 8,096 people were affected during the 2002-2003 SARS outbreak and 774 died.

By contrast Covid-19 spreads much more easily from person to person and symptoms can often be mild, making it difficult to identify potential spreaders.

There are also significant differences between Covid-19 and the seasonal flu.

With an estimated average mortality rate of 0.1%, seasonal flu is 10 times less lethal than Covid-19. Most importantly, a vast majority of the population is already immune, or at least partially immune, to seasonal strains of the flu. Vaccine and anti-viral drugs are available for the regular flu.

As Covid-19 is an entirely new virus, there is no immunity at all in the population, no vaccine and no drugs as yet, meaning that an unprecedented number of people may require hospitalisation, putting a great strain on the health system of any country.

Symptoms

The symptoms are fever, a dry cough and shortness of breath. Most people start showing symptoms three to five days after infection, but the maximum incubation period isn’t fully confirmed.

Fever is not always present at the onset and, reportedly, 40% of people who were admitted to hospital in China with Covid-19 did not have a raised temperature. Temperature screening is therefore not a useful tool to detect whether someone is infected, who might be sick, or who might still be capable of spreading the virus.

People in the same risk groups as flu are still thought to be the most affected. That includes people with existing medical conditions, including respiratory problems, but also those with diabetes, heart disease, kidney disease, the immuno-suppressed and, possibly, even pregnant women.

However, not all those who have died were older or had pre-existing conditions.

There have been no known cases of severe infection in anyone who is healthy and under the age of 20.

Transmission

Coronavirus is a respiratory virus and is present in secretions from the nose, throat, mouth and lungs. These secretions are exhaled, coughed, or sneezed out then inhaled. They can also contaminate any kind of mucosal surface such as the eyes, nose and mouth. Some of the larger droplets fall and contaminate surfaces. Tinier droplets can be inhaled and very tiny droplets will actually dry out and become like dust particles. They can remain suspended in the air for a period of time and be inhaled deep into the lungs. These dried out droplets can remain active for hours, or even days, though exactly how long is unknown.

With SARS, another coronavirus, victims only passed on the illness after showing symptoms, which meant that by isolating them the outbreak was brought under control. Diseases like measles, however, are harder to control because the virus can be spread without people knowing that they’re sick. This coronavirus may fall into this category, although this is not confirmed.

The easiest way to control the spread of the virus is by thoroughly and repeatedly washing your hands with soap for at least 20 seconds. If you are in an environment that is contaminated with virus particles, your hands must be clean before coming into contact with your face, nose or mouth. This is a key hygiene precaution that will limit the spread of the virus. Avoid shaking hands.

Scientists estimate that each person who is infected can spread the infection to an average of 2.5 new people.

Tests/treatment

At the time of writing, only government-authorised facilities are able to test for Covid-19. No effective anti-viral drugs have yet been identified but trials are underway.

Masks and goggles

Except in specific circumstances, face masks are not recommended for the general public, as they have not been shown to be protective in any measurable way in studies on the spread of flu viruses. Wearing a mask in wide open spaces, or generally outdoors, is also not useful.

There are however cases when masks can or should be worn. There are two main kinds of masks:

* Surgical masks: these are the masks most often being worn by members of the public, particularly in Asia where they were common even before the outbreak. They don’t offer protection to the wearer but are instead designed to protect others from sneezes, coughs or simple exhalation. Surgeons use them to avoid contaminating their patients. A surgical mask could be given to someone who is known to be infected or has a cough, cold or the flu in order to protect those around them. Look for a CE mark to show that it meets certain standards of fluid resistance. Fashion masks being sold over the counter with designs on them are unlikely to offer adequate protection.

* High filtration masks: the so-called N95 (in the US) or FFP masks (in the UK and Europe) are used in a medical environment for personal protection. N95 masks are designed to protect against 95% of particles of a 0.3 micron size (the average particle in cigarette smoke, for example, is 0.3 microns in diameter). The equivalent European standard is FFP2 and FFP3 which filters out 94% and 99% respectively. Masks must fit tightly. If air is getting in around the edges the mask will not work. Beards, for example, interfere with the contact between the mask and the edges of the skin. A high-filtration mask with a valve allows you to breathe out and to wear the mask for longer and be more comfortable but removes any protection for others.

If wearing a mask make sure not to touch the outer surface, contaminate your hands and then transfer the contamination back to yourself. In a contaminated environment like a hospital, put on and remove your mask only and exclusively by the straps and wash your hands every time you touch it. Most people don’t do this, making the use of a mask pointless.

Ordinary glasses or sunglasses provide a degree of protection from a cough or sneeze, making goggles unnecessary, except for those in a high-risk environment.

Contrary to common belief, the majority of modern, large airplanes are actually remarkably clean because of HEPA filtration and air conditioning systems which destroy viruses, even down to the size of coronaviruses. It is advisable to turn on the air vent above your head so the air can push any suspended particle to the ground faster.

Self-isolation

Self-isolation is different from quarantine. Anyone who tests positive for Covid-19 or has been in close contact with someone known to be infected by the virus will be kept isolated in quarantine.

Self isolation is a discretionary preventative measure that applies to people who have a higher chance of having been exposed to the virus. Individual government recommendations vary by country and are being regularly updated. Staff returning from assignments – or holidays – in countries where the coronavirus is more widespread and serious such as China, Italy or Iran are strongly recommended to self-isolate.

That means staying at home for 14 days, not using public transport and not doing anything that might expose others to the risk of infection. As much as possible, people in self isolation should keep to a separate room in the house, or at least stay two metres away from family members. They should also avoid sharing food or toilet facilities or be the last one to use them before disinfecting.

Viruses are destroyed by detergents, alcohol, extreme drying and heat, so these are all good ways to de-contaminate, especially clothing.

Newsroom safety/working from home

News managers at organisations with offices, staff and freelancers around the world are struggling with conflicting advice from health authorities in different locations, while at the same time covering a story for which there is a huge appetite.

Different governments have different recommendations or regulations about what to do in case a member of staff tests positive for Covid-19. At the time of writing, the UK and other countries’ regulations do not require, nor recommend, closing down an office or sending staff home. However, some members tell INSI they have taken, or plan to take, a much more conservative and cautious approach by asking staff to work from home if at all possible should an employee come down with Covid-19.

However, it is widely agreed that anyone who has any flu-like symptoms (coughs, cold, sneezes) should categorically stay at home. This might be a culture change in some organisations but no one should be going into their work place with germ-ridden hands or runny noses. Employers must keep people with cold or flu symptoms out of the workplace to avoid spreading the virus and the anxiety associated with possible contagion

Organisations should get prepared for large numbers of staff working from home, ensuring they have extra personal laptops and access to VPNs, for example.

For those in the newsroom, public areas, including hot desks, must be thoroughly cleaned with an anti-bacterial cloth or spray. That includes door handles, toilets, shared facilities like kitchens and computer keyboards and mice.

Employees should be vaccinated against flu. The vaccine does not protect against coronavirus but avoiding ordinary flu is a good way of reducing unnecessary anxiety, alarming co-workers or ending up isolated or quarantined for a preventable reason.

Many news organisations are reconsidering foreign deployments entirely and cancelling all non-essential travel. INSI members say this is made slightly easier by a lack of interest in stories other than the coronavirus which is dominating the news agenda.

Plans to manage staff safety at the Euro 2020 football championships, which are scheduled to take place all over Europe this summer, and the Olympics in Japan are still being developed, assuming these events go ahead.

Managing staff abroad

It is essential to get prepared. Make sure local staff know where to go for medical treatment should they get sick. In countries where medical facilities are poor decide whether a trip to the hospital for oxygen, for example, is the best approach, or whether evacuation would be preferable. Reach out to hospitals or public health authorities in advance rather than waiting for something to happen. Have a plan in place at an early stage so you are prepared if staff are infected. Take account of any staff members with a pre-existing condition that could put them at greater risk.

Interviewing recovered patients

People can continue producing the virus for at least 14-16 days after the onset of symptoms. Avoid interviewing or getting close to anybody within that period of time.

Sources: Dr Richard Dawood, the Fleet Street Clinic; UK government; INSI members

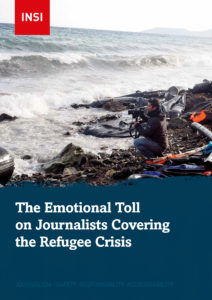

Image by AFP via INSI

Yannis Behrakis (pictured left) turned his camera on his home country of Greece where he began covering the story in April 2015.

Yannis Behrakis (pictured left) turned his camera on his home country of Greece where he began covering the story in April 2015.